AI vs. Humans - A Battle for the Ages

Our world seems to be increasingly crafted and influenced by AI - otherwise known as artificial intelligence. Whether that be the various dubious recommendations made by Youtube’s seemingly finicky algorithm, bail algorithm systems used by courts, or by Google ensuring you don’t click past the first page, it is evident that AI has helped massively in increasing our productivity and efficiency. Enough with cooperation, though - how does AI stack against mankind in head-to-head competitions? Let’s take a walk through previously human-dominated fields, and see how AI has matched or even exceeded human performance.

Games

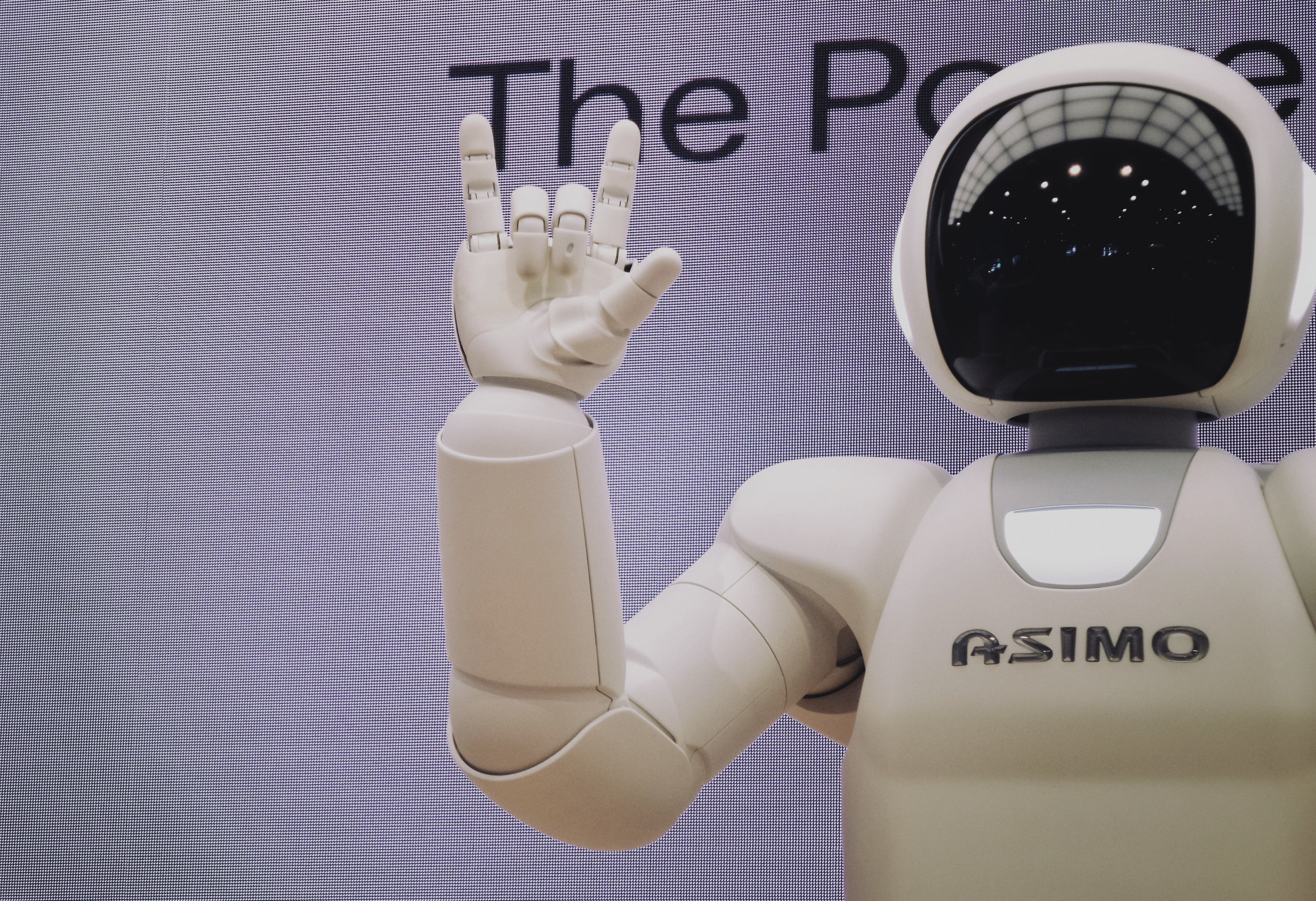

One of the more obvious battlefields for AI is in the realm of gaming - most notably, the ancient strategic board games of Chess. Without any further ado, let’s start with Chess.

Chess

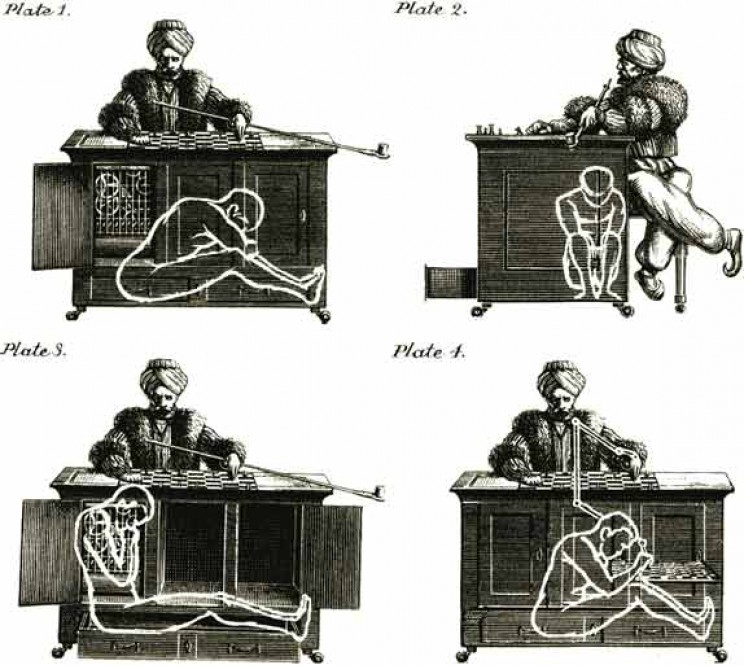

The origins of the human fascination of a mechanical mind playing Chess originates back to Wolfgang von Kempelen, a burgeoning Hungarian inventor. Then in attendance at Maria Theresa(the Holy Roman Empress)’s court, he and the audience witnessed Francois Pelletier’s amusing and bewildering tricks involving magnets and various chemical reactions. Theresa, being the curious and scientifically progressive empress, asked whether Kempelen could unveil the secrets behind Pelletier’s tricks.

Kempelen, so unimpressed by Pelletier, promised that he would return with an invention that would top Pelletier’s trickery. Just a year later in 1770, he kept true to his word, presenting a chess-playing android that consisted of a human puppet dressed up in Ottoman clothing sitting adjacent to a cabinet - which was coined The Turk. Shocking the world, his mechanical automaton even talked with spectators and rejected false moves that were ostensibly made to confuse The Turk.

A diagram depicting The Turk, the human inside, and how its mechanisms worked.

The only problem? The Turk was nothing more but an elaborate costume, dressed up in gears and cogs, concealing a small man inside that could observe the pieces’ positions via small magnets attached to their bases. The convoluted system of pulleys then allowed the small man to move the “arms” of the Turk and to grip and move pieces across the board. The Turk shocked and astonished crowds and even royalty in Europe. In 1805, it was sold to Johann Nepomuk Malzel, a Bavarian musician and inventor, who wished to tinker around with it some more. Eventually, Malzel died while on a return trip from Cuba, and after finding itself in the hands of a couple of amateur hobbyists, it lingered inside the Peale Museum in Baltimore, where it met its demise through a fire - its last words were through its artificial voice box, yelling “echec! Echec!”, meaning “check” in French.

The Peale Museum as it stands now in Baltimore, Maryland.

The field of Chess artificial intelligence went through numerous theorists and scientists who constantly furthered the limits of the mechanical mind, and combined with the increasing efficiency of computer processing and the heightened interest in computing, chess playing computers finally made a breakthrough with IBM’s Deep Blue.

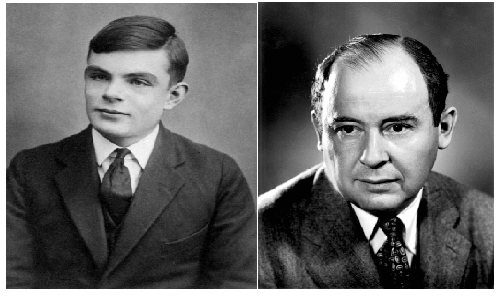

(Left) Alan Turing, a prominent computer scientist who played a significant role in cracking the Enigma, and designed and invented the Turochamp, generally considered the first chess program.

(Right) John Von Neumann, who worked with Alan Turing with regards to the philosophy of artificial intelligence. Proved the Minimax theorem, which was worked into the primary algorithm used in IBM’s Deep Blue.

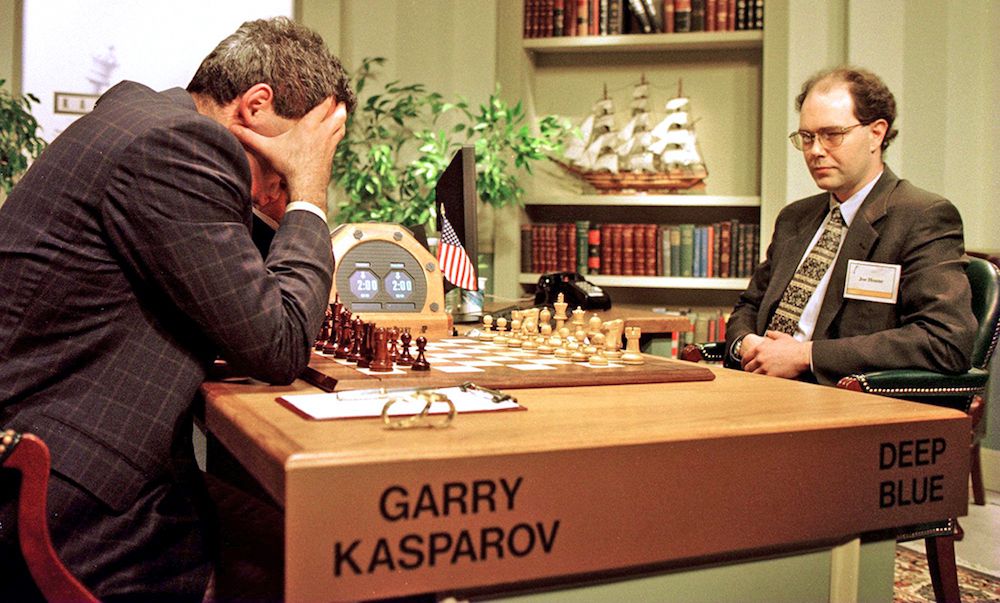

In the 1990s, IBM purchased a computer developed by a team of computer scientists at Carnegie Mellon University, which contained specially designed chips for discovering and evaluating chess possibilities - the system put together could evaluate an impressive 200 million positions per second. When Kasparov decided to take on IBM and its machine in 1997, he initially won the first game of the 6, but he then lost the 2nd game due to a blunder involving his queen. Eventually, Deep Blue won the six-game set against Kasparov 3.5 to 2.5, where it became the first computer system to defeat a ruling chess champion under standard chess timing.

A famous image of Kasparov playing DeepBlue, with an IBM employee relaying results from the supercomputer to the table.

Modern Chess AI

An image of a chess program using the popular Stockfish engine.

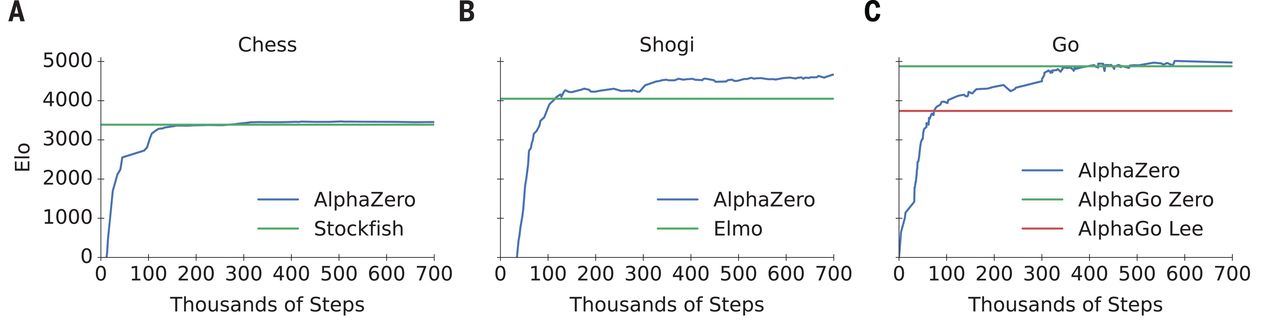

These days, chess engines have been developed that can easily beat grandmasters at their own game - the AI, with the gargantuan amount of resources of time and developer work put into it, far surpasses the outer limits of human chess aptitude. Furthermore, thanks to the ever-increasing efficiency of computer processing and sharply decreasing prices, these engines can be easily run in comparatively tiny smartphones and computers, a far cry from the towering Deep Blue that easily towered over the then-champion Kasparov. What’s perhaps more interesting than these engines are the applications of several companies to use neural networks to power chess AI; these so-called networks are called as such because of their somewhat superficial resemblance to its biological counterpart - the artificial “neurons”(also called perceptrons) that can weight its inputs and vary the strength of its connections to other “neurons.” Computer scientists train these artificial networks by using sample inputs and outputs, thus developing statistical associations inside the network from an output to an input. What is rather astounding about this process is that such systems learn to perform these tasks quite well, especially without having to be explicitly told the rules behind such tasks. In particular, Google has waded into the field of chess AI with its AlphaZero program. It has trained its internal neural network by displaying it with thousands of games from chess expert moves, and then afterwards using reinforcement learning - a type of machine learning where AlphaZero learns from itself via trial and error, learning which moves are beneficial and which are detrimental to its chess game. AlphaZero has far exceeded the caliber of “standard” chess engines like Stockfish and Komodo, and would hence singlehandedly obliterate any human at chess.

Graphs displaying how long it took for AlphaZero to surpass Stockfish in Chess, as well as other AIs in other board games, such as Shogi and Go.

Healthcare

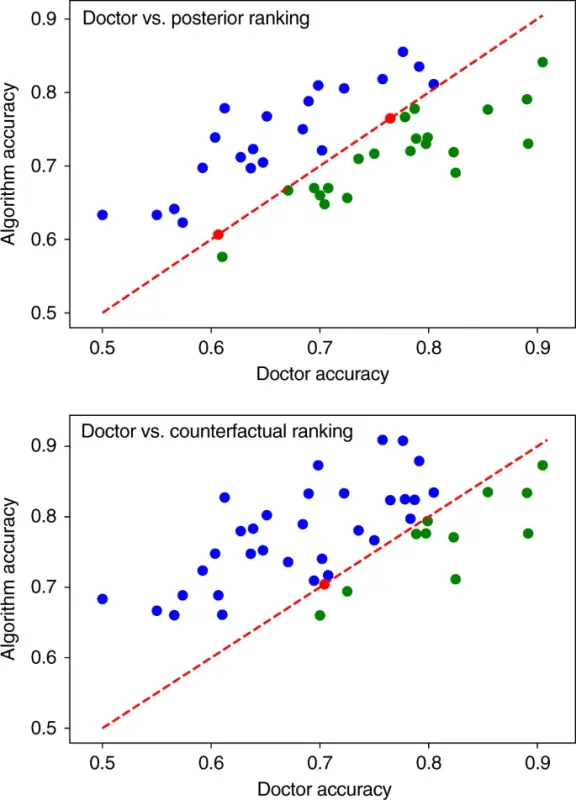

Similarly, machine learning models have also been applied at various medical tasks - one of the more important ones being the diagnosis of illnesses. Misdiagnoses and missed diagnoses still plague prosperous countries such as the US, although accurate statistics for misdiagnosis rates are hard to come by, some experts put the rate as high as 5%. Some other studies put that approximately 12 million people are affected by medical diagnosis errors each year in the US, and that a shockingly high number of people - 40,000 to 80,000 - die each year due to medical misdiagnoses in U.S. hospitals alone. Unfortunately, the actual number is probably higher, due to the lack of actual mechanisms that patients can use to report misdiagnoses. Traditional diagnosis algorithms have had lower accuracies of diagnoses, as they use an approach that identifies diseases that are most associated with a patient’s symptoms and medical history; this approach generally runs counter to how most doctors diagnose their patients, which is generally done via suggesting diseases that best fit with explanations for the patients’ symptoms. In a peer-reviewed research paper done by Richens et al., this new approach utilized by machine learning yielded an exceptional 77.26% accuracy, which put it in the top fourth of all doctors. The machine learning approach also did substantially better than its human peers at rare diseases.

The traditional(or posterior ranking) which had been used previously in other algorithmic approaches. Below, a counterfactual approach, which was used by this machine learning algorithm. Blue dots above the lines in both figures represent doctors that were less accurate than the AI. Green dots below the lines in both figures represent doctors that were more accurate than the AI.

The astounding success of machine learning(or AI) in healthcare cannot be understated. According to the WHO, nearly half the world has virtually no access to healthcare - and a swift AI ‘doctor’ could make a massive difference in mending the massive inequality that exists in our world.

Hopefully, these two examples - chess and healthcare - help you appreciate the immense amount of power that AI has over humans, and how the might of trillions of operations crunched every second by a computer, coupled with data and a bit of assistance from mankind, can greatly assist our relatively slow human brains in our everyday lives.